|

|||

| Home Books Admin | |||

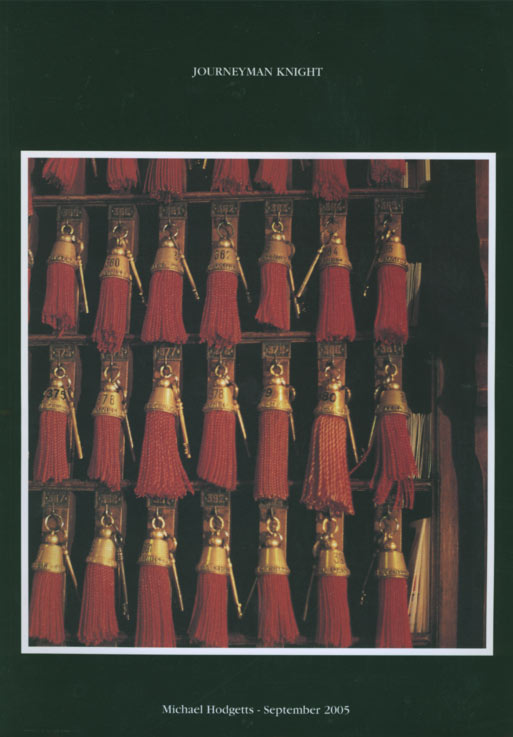

Mark knew he was asleep and dreaming. He guessed it was a dream within another dream, that rare phenomenon we experience when we are in denial or shock. The trick was to know how far down in sleep he was and when he was awake. Was he awake now or in the final dream? He had been thinking about 'The Wind in the Willows', the stories of Ratty, Mole and gruff old Mr Badger, wise old Mr Badger. And the Weasels and Ferrets. And Toad. And the title always taken for granted. "The Wind in the Willows." Mark thought he might be in Christchurch, New Zealand. Endless streams and rivulets, criss cross the urban garden that is Christchurch. Wild ducks stroll on the lawns, each block is divided from its neighbour by wind breaks of quick growing trees, especially willows, bowing as part of nature's welcome committee in this most gracious of cities. Farmers plant wind breaks to cut and reduce the impact of the mad winds screaming out of the snow capped mountain spine, down, to and over the Canterbury Plains. Getting ready for bed, listening to the roar, Mark had asked about the noise they heard just as the sun went down. A sort of sustained whoosh. - Have you never heard that before. It's the wind in the willows. The wind in the willows! These and other comforting thoughts murmured on the hob of Mark's mind as he struggled out of one level of a deep and satisfying sleep. He was on a plane. They had just landed. He had slept through the landing. He didn't move from his seat immediately, happy where he was. Content to let others struggle and compete, those with a mission, an urgency he did not feel. People leaving planes are always in a hurry. It's a sort of competition, a compulsion. The plane will self destruct shortly after impact. Mark had a window seat and the man beside him, tall and fair, was standing up, getting a few things out of the overhead locker. - You slept well, he grinned down. - You must've been tired. You slept right through the landing. You must be very relaxed. But Mark had been listening to 'the wind in the willows' just before he had woken up. Was that the plane landing or his mind creaking? Mark liked to sleep. He had given up drinking on planes and felt better for it. Drinking on planes makes you drunk. He'd been feeling quiet and withdrawn. He often was these days, not talkative. Most people on long haul flights have their cabin plans worked out: watch a couple of films, prepare a report, catch up on the business papers, get ready for the meeting, read that book. In Mark's case, to sleep, perchance to dream. Layers of dream in fact. Mark's blazer and yet not Mark's blazer. Not the one he had expected. At first he thought some other diner from Sydney had gone off with his. Then he realised what he'd done. If ever Mark lost enough weight, it was good to know that hibernating in a Christchurch wardrobe was a spare. The front of the plane was emptying. Two flight attendants had their backs to economy. Mark got up and left the plane. There was Jim from the Olympic Games over on the other side of the plane. Mark waved and said - Hi Jim. Jim waved back. They walked out together. Jim was holding out the boarding pass to get through the first of the security turnstiles they now have in airports everywhere. Mark had forgotten to get his boarding pass ready. That's why he didn't talk so much. He needed to concentrate. Jim, Mark noticed, was growing his hair longer. It suited him and he said so. Mark kept up a chatter of comment as he pulled out his palm size wallet purchased in the market in Florence. In the middle Mark kept loose currency notes and Visa receipts for filing. It was untidy but they were all in one place. His Senior's Card and Credit Card were generally there too. Sometimes he misplaced them and panicked. He was panicking now. - Oh God. Which one is it Jim? Jim looked down. Mark was holding up the flow and he was probably in a hurry. - There it is. And by the way I'm Christopher, Jim's son. Must dash. See you. Jim's son had pointed to the small white card with longitudinal grey stripes on each serrated edge. They left the plane, through the first turnstile, into the air bridge, then through the second turnstile from the air bridge up the steep rapid escalator. To access the one person wide escalator, one by one each of them had to feed the card into the slot. It was a good way to control crowds but it slowed people up. Some like Mark would misplace their card once they were in the plane and he was glad of younger eyes. The escalator took them upwards, Mark supposed about two storeys. They were now in a large square holding room, more spacious and less confined after playing at sheep going through the dip. Or moles in earth tunnels. Mark had an awful thought. He didn't feel right. He was travelling too light. Grey flannels, black shoes, white shirt, striped navy tie, blue blazer, palm size wallet. No brief case, no duty free grog, no shopping, no personal travel bag. He had never travelled so light in his life. Oh God, he must have left his personal things in the overhead locker or down beside the seat. What an idiot. He should never talk to people when he was trying to concentrate. His brief case? Where did he put his brief case and his passport? A dread feeling of fear and incompetence started to rise from the pit of his stomach. Oh God, he didn't have his passport. All the travellers were filing quickly through passport control. Green blue red passports. European Asian African travellers. Get ready for inspection. An efficient orderly civilised plane load of experience. And one aged white haired idiot who'd left all his carry on things back down the escalator on the plane. Mark went and sat down on a single seat. This was a real worry. He was confused. He had to remember what he had brought on to the plane with him. Did he have a suit hanger? Christ! Where was he going? He couldn't even remember that. All he had were the clothes he stood up in, reasonably tidy. And his credit card wallet. At least he had his driving licence. It would act as an identity card. It was a nightmare. A nightmare? Could he still be in a dream, if so he wished he would wake up. The staff were speaking English. Thank God for small mercies. Somehow he had expected they would. They were dressed in standard navy uniforms. He had better get some help. What did he leave on the plane? In the overhead locker. Blank. Briefcase: black plastic leather. Thin standard size, leather strap handle. Long shoulder strap. Single brass slide clip. Bank books, reading material. Some business papers. It was a light case. Pretty empty considering he was travelling. Probably had medication in there too. Adrenalin Puffer in case of emergency, Zocor for cholesterol, Claratyne for anti-histamine. Did he remember a white plastic shopping bag with some soft things in it. And another plastic bag with some books? Did he have a suit hanger? Blank. Duty free grog. He didn't drink much any more. Had he bought any as a present for anyone? Who was he visiting? Where was he going? He still couldn't remember. Where was he? Help. Now he was really in trouble. Where was he indeed? Blank. He couldn't remember. In any case, why did he not have a flight ticket? Wasn't this Qantas? He always kept tickets, travellers cheques, passports together. Passports, he remembered he had two. One blue Australian, one red European. Where were they? He went to a female attendant standing to one side, carefully watching the moving passengers. - I think I'm in trouble. She smiled. - If you are, we're here to help you. She was a nice person or had graduated at charm school. So nice, so helpful, a hint of an accent, Scottish or Irish. Was she customs, health control, police? Were they in London, New Zealand, the USA, Holland or Scandinavia? - Just come to the desk, please, Sir. Mark pulled out his driving licence. - This is who I am. I've just come up from the plane. I feel such a complete idiot. I was talking to a colleague I met as we were standing up. Hadn't seen him since the Olympic Games in 2000. He was one of the organising bosses. We came off together. Then he told me he was actually my colleague's son. - I've left all my personal things on the plane. I'm so sorry. I feel such a dolt. I am a dolt. She touched Mark's arm comfortingly. He could see her thinking, nice old man, well spoken, seventy, doesn't fly much these days, probably used to be important, flying all the time. Got confused. Grandfather type. She smiled. - Have a seat, Mr Hammond. She'd written down his name. It was nice to hear her say it. It made him feel human again. Hammond. Hang on to Hammond, Mark Hammond. - Have you got your boarding card. He gave her the grey striped, serrated edged boarding card. She wrote down the number, gave it back to him. - Please don't lose this, Mr Hammond. She looked hard at Mark to see if he understood. He nodded. Took it back, held it tight in his hand like a child with a toy. - It's your computer identity. Without this, on this airline you don't exist? That was a worrying thought. Mark had been beginning to wonder if he did exist. - It helps us recover your cases from the baggage lobby. Just wait here. The crowd had thinned. Only stragglers were left, and Mark. It had not been all that big a plane. Mark didn't know the different types since the airlines merged. He looked through the double doorway where the leaving passengers were going, into the main part of the airport. Working her way across the tide of the crowd, was a tall young woman, threading her way from one side of the door opening to the other. She must be a passenger coming back. She was wearing a white and navy blouse. Tanned, tall, thick bunchy hair, fair, frizzled, put together at the back like a large handful of corn stalks. Skirt navy. Shoes navy. The first female attendant came back with a suited officer, tall and fair. - Hi there, I know you. Remember me? I sat next to you on the plane. It was the man Mark had exchanged a few words with. Now he was a captain. He'd changed into uniform. - I didn't know you were with the airline. - No, he laughed, - well, I am. - I hope I didn't say anything unkind. - No, you didn't say much at all. I like that. I understand you have a problem leaving your belongings on the plane. Just sit there. We'll get it sorted for you. Someone's down there now, checking your seat and the overhead locker. And the wardrobe. Mark did not feel relieved. He was not convinced they would find anything. Not even his passports. - Thanks a lot, he said mechanically. - Trouble is I feel ashamed, confused and inadequate. I can remember, I have two navy cases with red straps round each. But I can't remember where I put my ticket and passports and travellers cheques. I know this is Qantas, but I can't remember where I'm travelling from or to. And I can't remember the date. - I don't even know where I am. Mark was close to tears. They looked at him noncommittally. The captain lowered his voice to indulge and soothe an old man. - It's not Qantas, Mr Hammond. As he said those devastating words, Mark felt he became a stupid child and the captain was the patient kind older person. - We are called 'Alliance'. - You'd better come with me, Mr Hammond, just through here, the girl said - I'll get you a nice cup of coffee. You'll be more comfortable, away from everybody leaving. You must be feeling quite upset. The captain left, he'd a plane to fly. He shook hands before he went and said - it'll be okay, Mr Hammond. We've never lost a passenger yet. It was supposed to be a joke. - Where did we just fly from, please? Mark spoke in a small tremulous voice. - Sydney, he replied, raising an eyebrow and looking across at the 'Scottish' girl. - Where are we now? - Heathrow. Did you really not know? Mark was now in a comfortable VIP Lounge and a man closer to his own age was talking to him. - Mr Hammond, it's lucky I'm here. I only do Mondays at the airport. Please fill in this short form. Basically it's a claim for lost property, but it also tells us a bit more about you, your medical history and so on, in case it turns out you have some sort of medical problem, memory loss, amnesia. You seem quite sane to me, he smiled reasssuringly. - But we do need the detail. There's obviously a problem here. We've not been able to find anything that belongs to you in the cabin, no suit or clothes. And there was nothing left in the overhead lockers above and behind your seat. There was nothing under any of the seats either or in the seat pocket. That means if you did leave something on the plane, it must have been picked up by someone else which is not something we like to have happen. We can provide you with personal items, shaving things, pyjamas and so on, and money for a shirt. I expect you've heard this is what happens when baggage is lost. We've been down to the carousel and there's nothing down there of the type you said. No navy cases with red straps. Could you have had them last time you travelled and are remembering that? Mark was beginning to feel irritated by this 'doctor' who was basically telling him he was a nut case. Or suffering from some sort of breakdown. Or still dreaming. The Scottish girl knocked on the door. She seemed happier about something. - Excuse me interrupting, Mr Hammond. We ran your name through the airline computer. We found you all right. But you came up with an unusual linkage. Do you know a Doctor Gabriel Basler? - Yes, of course, Mark said. - He lives in Melbourne. - Your name was tagged to him as a reference. We punched in his name. You're on a schedule on his file. You don't need a passport, Sir. It says Mark Hammond, Cardinal Wolsey School, Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, Freeman of the City of London, Journeyman Knight. You're a Journeyman Knight, Mr Hammond. Welcome home. Journeyman - qualified artisan who works for another Mark could now remember Cardinal Wolsey School and he also remembered Gabriel Basler. His memory seemed to be clearing. Like the morning fog, it would take some time. But perhaps he was still asleep, dreaming, just moving out of one level to another. He knew Basler had been one of Melbourne's leading heart surgeons, lived in Mornington. Mark had first met him years before when he was in the Government. Gabriel Basler had given Mark some assignments on occasion. Yes, he was a Journeyman Knight. It was a term he'd also applied to his own father. Father had done very well in the War first with the Norwegians, then the Dutch. Perhaps these concepts ran in families. The Scottish lady was talking. - More good news, Mr Hammond. We found two cases which have your name and seat number on. They are coming up right away, save you the trouble of collecting them. And your customs, health and immigration checks are done. Because of the confusion, we've arranged to take you out through the Government Channel. And your grand-daughter, Elizabeth, is waiting for you. Can I bring her in. She came to meet you and was worried when you didn't show up. So sorry we didn't know you were coming. We'd have taken much better care of you, Sir. The 'doctor' was looking put out. He'd been enjoying his moment of patronising glory. Playing cat and mouse with a senile visitor from Australia. Probably it compensated him for the cricket. - Nice cases too, Mr Hammond. Not navy blue with red straps, she smiled indulgently. - You must have been remembering an earlier journey. But the most expensive looking Samsonite light weight stainless steel. I must say you have excellent taste in luggage. She smiled. Mark nodded pretending he was in complete control. But he had only ever had one Samsonite briefcase 45 years ago. And if he had a grand-daughter called Elizabeth, that was news. Still it would be better to play along. At least he was rescued. A tallish girl came in. It was the flaxen haired beauty in navy. For a grand-daughter she was very acceptable. - Grandpa, she cried and rushed forward. She embraced him, feeling soft and cuddly and feminine, smelling of Lilies of the Valley. Mark held her close. He was not dead. - Little Lizzie, it's been so long. How you've grown. How long is it now, since I last saw you? His sense of humour was coming back. The Scottish lass secured a strong looking Indian porter who'd driven up in a mobile bus for five with baggage space on a flat top at the rear. Lizzie and Grandpa climbed aboard and the two employees of Alliance Airlines waved good-bye. - 'Little Lizzie'? She rallied. - My name's Elizabeth and that's what you should call me. - Okay Elizabeth, Mark apologised. - Where to now? - Heneage House, she said. - Remember it? - Of course, the best. It's where I used to stay in the old days. - I know. It's why we put you there. We thought you'd feel at home. - And how are your dear mother and father, Elizabeth, and where are they these days? What does your father do? You won't believe this, but I've quite forgotten. She laughed. They were emerging down a ramp, out on to the external doors. She picked up her cell phone, pressed a number. They stopped and the Indian porter unloaded two smart looking light weight Samsonite cases. - They're not too heavy, are they, Mark asked him conversationally. He smiled and in broad cockney replied - No Guv, light as a fevver. A black, highly polished Rover slid into a position at the kerb, reserved by a quartet of bright yellow witches hats. A bearded policeman stood nearby looking vaguely protective. As Elizabeth glanced in his direction he nodded slightly. They were ready. Mark went to tip the porter, found he'd not yet acquired British cash, nor any other money as a matter of fact. - Look after the porter, dear girl, he said in an English accent. - I seem to be momentarily out of change. She gave him a look and slipped the porter a note. He touched his cap and winked at Mark. - Nicely, Guv, he said, - fanks a lot. 'Ave a nice sty. The driver said 'Good Morning Sir'. A young man beside him said nothing. Elizabeth and Mark were in the back, the arm rest between them. Mark's two new cases were in the boot. Elizabeth opened her navy hand bag and passed Mark a wallet. He looked inside. One red European passport valid for eight years with his photograph looking younger than he felt. The details were correct. It was either his passport or a superb copy, and who'd want to copy it if they had the original? Secondly his up to date Australian passport again with the right visas and records of trips to other countries. There was a useful sheet listing the injections he'd had, including Typhoid, Tetanus and Yellow Fever and all the Hepatitis jabs. He could go anywhere. There was an envelope with travellers cheques with his signature in the top corner as required. And about a thousand pounds in used notes. - Gee thanks. Feels like my birthday. - It should, she said seriously. - Here are the keys to your cases. You know the combination. Mark did if it was his birthday. He always used those numbers. Mark talked to the driver about the car. He was pleased with it. Not so pleased that Rover, Jaguar and Daimler were all owned by foreigners. - We lost the plot, Sir. What wheels do you drive in Australia? Mark explained after a Mini, and an Austin 1100, he'd graduated to a Holden, then two Triumphs. On his forty-first birthday he'd bought his first Jaguar. he'd had three in the end until the last was stolen. The insurance was not enough to replace it. - So I bought a BMW. Now in my autumn years I drive a gold Nissan Maxima. Now how could he remember that? - Good cars, the driver conceded. They were crawling through the top of Victoria Street just past the Station. It was past the full evening rush hour, but traffic was still heavy. - I used to walk down Victoria Street before I emigrated in 1962, Mark told him. They were stopped in traffic just across from the big department store. The lights went red. Looking over at the store Mark, a young man in a balaclava, opened one of the side doors, carefully looking out. He had a shot gun under his arm, seemed nervous and amateurish. - What time do the stores close? - Tonight? About now, Sir. - I think there's an armed hold up going on. D'you have weapons in this vehicle? I had three years in the Royal Navy working in Military Intelligence and with the Naval Police. I had small arms training to Marksman Level. The driver hesitated, looked at the store, saw the man. He pulled down a panel across but under the dashboard. - We have one rifle, Sir, he said. - You sure you want to do this? - And a pistol, grinned his offsider, referred to as Roger. Speaking to Mark for the first time, Roger said, - let's go and have some fun, Sir. Elizabeth put her hand on Mark's arm. - It's none of your business, Mr Hammond, she said. Mark was now convinced he was still asleep and that the dream was taking a turn for the better. He'd nearly volunteered to be a freedom fighter in the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. He'd almost been retained in the Navy at the time of Suez. It would be good to take up a real challenge. - Better an old man in his last carefree years, than a young married constable with a wife and three small children. He felt young and invincible. The driver's mate, Roger, took the pistol, passed Mark the rifle. The driver showed Mark how to load the magazine, there were only four bullets with clean copper bottoms. Like new saucepans, he thought. Not much fire power if you compared it with the nasty weapons they used in the war films on television. Mark checked the safety catch, looked at the magazine. - Four rounds? - Yes, Sir. Only four. It's for emergencies. - You'd better call the Armed Robbery Squad. The driver was already talking into his radio as the two of them ducked out of the Rover, raced across Victoria Street between the stationary cars. They could easily cross without being seen. With weapons concealed, they strolled casually up to the door. Mr Balaclava looked out again for the third time. The gun came up and Mark poked it in his face. - First round goes between your eyes, he said. - Put your gun on the floor, kick it outside. He did what he was told, seemed relieved not to be playing any further part. - Now lie on the floor with your hands behind your back. Roger handcuffed him neatly, he'd done this before. One gone. Two men with hand guns were holding up the frightened shop girls, and a third man stood at the jewellery counter. Expensive stuff there. A second assistant was opening a safe. - Roger, put the pistol away and hold Mr Balaclava's gun at his head. Ever shot anyone dead before. - Yessir. - Good. If you have to, do it again. - Yessir. Mark called out loudly : - There are armed men all round the store. Slowly and deliberately he walked to the two armed men. There might be more, but he had to start somewhere. He felt inspired. It was like a film. - We have your friend Balaclava as hostage. Don't try and make a fight because we're not police and I haven't killed anybody today, yet. You know Victoria is a State in Australia and you should keep out of Australian Territory. This is my patch now. Throw your guns down and lie on the floor. In a minute before the police come, we'll let you out the back. But do it now because I'm a mean impatient baaastard. He let the 'a' sound lengthen to emphasise he wasn't just some soft Pommy Policeman. Then he told the two not to take any chances. The two hand guns dropped and they lay down. Mark picked up the guns and put them in his pocket. His blazer was sagging with the weight. Might have to get a new blazer after this. The girls were looking at Mark, the man at the safe had stopped. - Shut it, Mark said. - Sit on the floor behind the counter, there may still be shooting. - Who are you, one of the London boys on the floor asked. - Ned Bloody Kelly, Mark laughed gaily. - Now, he pointed the rifle at him, - call your mates inside. He glared defiantly at Mark so Mark fired a shot into the floor between him and his partner. He phoned. - Tell them to come inside, I'm getting cross. Two boyish looking accomplices appeared after he spoke on the cell phone. One still had his phone in his hand. - Good. Best way out is the way we came in. Off you go number one. Mark pointed at the guy with the phone - leave that here. He left, staring hard at Balaclava who was face down by the door with Roger's gun at his head. He opened it, looked out, looked back one last time and was gone. - Next please, Mark called. One of the other prostrate prisoners lifted a hand. - Get up slowly, Mark said. In turn, he walked to the door and disappeared. - Number three. Another went. Suddenly in through four other doors armed police came in, armed to the bloody teeth. - Police. Police. Police, they chanted all rugged up in their protective clothing. Roger explained to a senior officer by the door why he was found with his gun to the head of Balaclava. He showed his warrant card, the senior officer motioned to another. It was over, Mark was not violent. Well not by Australian standards. Tensions relaxed. An armed constable gently took the rifle away from Mark. - Perhaps I'd better look after that, Sir. Roger was grinning from ear to ear. The girls were looking at him with adoring eyes. - You a copper then, luv, one asked. - Yep, he replied. - Bloody marvellous, said the man who had been opening the safe. - Thank you, Mr Kelly, thank you, he said. - Mr Kelly? Asked Elizabeth. She'd just appeared with the driver who had parked his car on the pavement not wanting to miss the fun. - It's an old Australian story, Mark said. - Should we be getting to Heneage House? I feel like my tea, Elizabeth. Mark Hammond was still bubbling with adrenalin. Every so often the driver or his offsider, Roger, would chuckle silently and Mark would smile in happy agreement. Elizabeth was still cross with them. - You should have had more sense, she scolded. - It could have gone badly wrong. You could both have been killed. - Look at the trouble we've had with bombers, she said. - You could have been blown up. - It wasn't that sort of thing Elizabeth, Mark said finally. - Look I'm delighted to have you as my new granddaughter but for God's sake do let up. She put her chin down into her coat and looked away out of the window. Soon they would be at Heneage House and she could get rid of this geriatric idiot from Australia for a while. With excitement interest and anticipation, Mark set both of his new cases on one of the two Queen size beds in his elegant room above the stables. They could not have been more thoughtfully equipped if Jeeves had packed. A toilet bag contained plastic razors, a Badger Hair shaving brush, his favourite shaving cream and toothpaste. In a matching medical bag someone had obtained a green packet of Zocor, a new Adrenalin puffer, a large file of anti-histamine tablets. There were creams for hand and feet in case of a re-occurrence of psoriasis. Whoever had attended to this knew Mark well. There was a prescription for additional Zocor with five repeats. It was a real secret service job. Mark could not decipher the doctor's name but the address was in Melbourne. Doctor Basler came to mind. Another Basler assignment? How many Journeymen did he have at his disposal? Mark asked for his long suffering blazer to be sponged and pressed in time for breakfast. He had a light snack and went to bed. Next morning he selected a pink striped Hilditch and Keys shirt and a bold pink and black tie he would not have bought for himself. The label inside said Henry Buck. Black shoes left outside the door, had been shined to military perfection. Memory was coming back in episodes. Back in Heneage House, he recalled other visits over the years. He knew the underground Elizabethan cellars, where celebrities sheltered during the Blitz, the cobbled yard and stables now converted to superior accommodation, the archway to St James' Street, and in the other direction, the narrow passage to Green Park. On arrival the police driver had whispered to the hall porter with an imposing top hat. In a loud voice the porter had called to his boys - look lively lads, Mister Hammond is back from Australia. As Mark got out from the side nearest to the hotel entrance, he held the door for him. - Welcome Home, Sir. Elizabeth was getting out the other side and he greeted her too. Mark was whisked through registration with a simple signature. His bill was being paid by some authority but not by him. Anticipating breakfast was a delight. You said what you wanted and it came, in silence. You were not supposed to speak. Reading the morning papers next day, one or two guests laughed. Between porridge and eggs, Mark glanced at the headlines. They were variations on a theme. The imagination of London had been captured. It was much more fun than terrorism. AUSTRALIAN GANG SURPRISES ROBBERS In Victoria Street last night, staff members were fearing for their lives from It was a perfect June morning. Mark had always enjoyed London in June. He stopped. He'd been heading for the front door of the hotel to get a breath of air. Now he wondered if he were a prisoner, if he'd be allowed to go beyond the portals of sophisticated confinement. One young porter was sitting at the desk reading the sports pages of a very small paper. He nodded to Mark and said 'G'Morning Sir'. Behind him were pigeon rows of key rings, brass bell shaped tops with skirts of red tassles. One antique key ring for each room, it was art as well as function. Mark said 'Good Morning' and passed through the stately front door. Turning right, Mark went up the close a few paces; yes, the alley was still there, slightly smelly, but dry in summer. He emerged into bright sunlight reborn between two gardens that backed on to Green Park. He was back in Green Park. To the right and left the wide hard surfaced drive went up to Piccadilly, down to The Mall. But a big change had taken place. Green Park which had once been pasture then for a hundred years or so a green sward of grass and trees dotted with deck chairs and recumbent couples, was fenced and returned to nature. The grass was cropped by black and white Friesian cows. The trees seemed to have grown in magnificence. There was not one deck chair in sight. Mark liked the change. Whose cows would they be? The Express Dairy who milked them in sheds down by Hyde Park Corner? Or perhaps the cows belonged to the Monarch, like the swans on the Thames. Mark stood looking, decided to turn left downhill towards the Mall. He could then go up the Mall for a hundred yards, cross to St James' Park; have a look at the view of Whitehall from the little bridge across the lake; retrace his steps, walk past St James' Palace and then round the street; back to Heneage House from St James' Street, through the archway and across the cobbles; into the back door and the Cocktail Bar. The bar was not yet open. He would sit in the lounge and see if he could get a pot of coffee. That sounded civilised. One of the alleys to the Park from St James is called Milkmaid's Passage. Mark recalled how milkmaids had become familiar with the sons of the aristocracy offering early drinks of warm milk after a night of carousing. The Dukes Hotel had once been a block of flats for young gentry. Mark's father popped back into his thoughts. He had been a complicated man. He should have, would have been a scientist, was obsessed by radio and communications. Mark thought, not for the first time, he should have lived in our time. He'd have been up with computers, E-mail, and the Internet. Right up his street. Instead, at fifteen, he'd matriculated, shoe horned into the Bank, had given the Bank his life, except for seven years in the Royal Navy. Then he'd really come alive. Taking part in so many theatres of war, having so many adventures, taking his camera, bringing back photos of explosions of water, prisoners picked out of the sea, profiles of ships served on, all carefully censored so armaments were obliterated by ink. Fleetingly Mark recalled some of the stories. Ah, he could remember them too. His mind was in an extraordinary state. Each clue revealed a new chapter of thought. Once revealed it stayed with him. And each thought left Mark with another set of clues. He had been wondering, not without a tremor of fear, if perhaps he had Dementia; that he was on a slow path to insanity. Yet so much had come back. He was encouraged, happy even as he walked along The Mall, shoulders back. He straightened his posture, swung his arms. Then in time to his walking, he started to sing a song. It was the old Song they used to sing at camp fires: Sandy Paterson, Dick Smith, and Mark. And the rest of them. 'Green Grow the Rushes, Oh.' Mark could suddenly, in another blink of his internal computer, recall those heady days of boyhood Scouting from twelve to fifteen. Curious verses sung without guessing the meaning. He went through them to see if he could get them back, after fifty years. One is One, and all alone, and ever more shall be so. To make greater sense they were sung in reverse order, which happened in the chorus. 'Four for the Gospel Makers' : Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. He knew he had once done research into the rest of the verses. He couldn't recall it all at the moment. He crossed into St James' Park, to stop and stand in the centre of the bridge. He had done this in October 1962. It was an 'Indian Summer'. Golden days and warm nights went on from August, through September. They expected October to be cooler, but October was fine. Even the first days of November were surprisingly mild. Why? Because Mark had applied for a job in Australia, a contract for two years. God and England wanted Mark to go with a spectacular memory of his last summer. - Goodbye Mark. Best wishes from us all. Love England. And he had gone. Spectacular! How hard up all his friends were in England; the awful weather; the country seemed riddled with class differences. Mark wanted to tan brown. Like Fay did. And one day, he wanted to have his own firm. He guessed if Australia were rebuilding its capital cities, the Australian construction industry offered a greater future than England. An inspiration at 25. Time to go back for coffee. The young porter had gone. The Head Porter was back. - Morning, Mr Hammond. Lovely day. Been for a constitutional? Your mail is here, Sir. You might like to read it in the lounge. I could order a pot of coffee. White is it? The lounge is nice and quiet at this time o' day. The Vacuuming's done, Sir. How I hate that noise, Sir. Good Lord! Mark had received a white invitation card with gold edging for a formal dinner at the Guildhall, three weeks on. And a second envelope contained a note from Elizabeth. She'd two seats for a concert at the Festival Hall for tonight. This afternoon she hoped Mark would take her to an art exhibition in Burlington Place. 'I'll collect you at three.' |

|||

|

|||