|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home Books Admin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

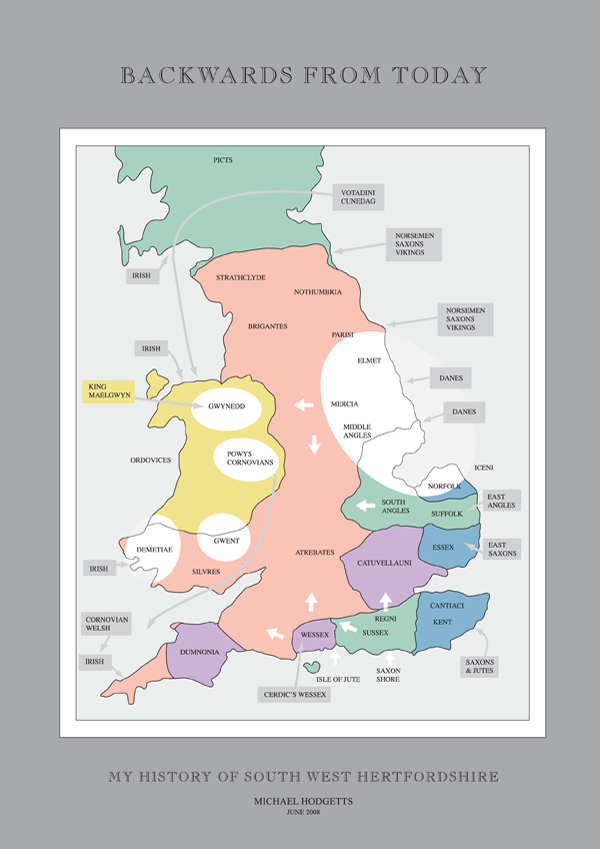

1. My History of South West Hertfordshire Many Saxon names are remembered in the district. They include Baecce Batchworth, Crocca Croxley, Aelde Aldenham, Caege Cassio, Gaete Gade, Ryckmehr Rickmansworth, Wippe Whippendell, Hanne Pole Mulle Hampermill, and possibly Eada for Edeswyk. With acknowledgements to H Weldon Finn - An Introduction to Domesday Book; and Keith Bailey - The Middle Saxons in The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. We tend to accept the county system in place when we were young without question. Yet the study of Domesday Book confirms a number of anomalies. The clerks struggled with the remnants of at least three legal systems, Mercian, Wessex and the Danelaw. New counties like Oxfordshire and Buckingham 1010, Northampton, Bedford and Hertfordshire 1011, Warwicks and Gloucester 1016, and Worcester 1038 had been formalised in living memory. Anglo-Saxon charters from 793 refer to Cashio, Rickmansworth, and Oxhey. In S1497, (990-1001), and S1517, (1053) both Watford and Hertfordshire are mentioned. Initially this suggested the name Hertford Shire predated the 1011 reference, and it was concluded Watford was included within Cashio for the DB survey. But recent thinking is that S 1497, the will of Aethelgifu, refers to Watford in Northants. And that our Watford did not exist as a settlement in 1086. If this is correct we defer to the 1011 reference. Aerial photography seems to prove the theory that in parts of Celtic Britain the established field patterns predated the construction of Roman roads, such as the territorial boundary of Fosse Way. Large scale fields are arterially truncated but the original field boundaries continue on either side. (Time Team Programme 16 May 2006). Importantly it is the independent and factual information provided by the Domesday Survey in 1086 which gives us the first solid foundation for understanding the development of England after the Roman Occupation of Britain which finished in 410 AD. Tribal Hidage – the list of Middle Anglian tribes who comprised Original Mercia Assessments in hides were made from an early time – Bede 731. Anglo-Saxon kings extracted labour and resources for projects such as Offa’s Dyke in a form of ‘national service’ which could be military or civil. Tax assessments, in money or in kind, were also assessed on a per hide basis in later Anglo-Saxon England. The charters of Offa confirm the proposal that the Middle Saxon area was a ‘provincia’ of Mercia, and that it included the later county of Middlesex. The area was smaller than that of the Middle Angles whose combined entries in the Tribal Hidage total 17,100 hides, exceeding Kent and more than twice the size of smaller kingdoms like the South Saxons and East Saxons. But ‘Middle Saxons’ are not mentioned in the Tribal Hidage dating probably to 670-690. They might have related to unidentifiable tribes. It is most likely they were simply included in a more dominant group such as the East Saxons, to whom they owed allegiance at this time. The East Saxons held 7000 hides; Essex seems itself to be about 2700 hides; and, for example, the Middle Saxon province was 1400 hides in 1086. My professional exams required an early study of the law of property, and looking back through the shelves of history, it occurred to me a system of land titles and demarcation was unlikely to be reconstructed by a conquering force. The owners might be displaced but the delineation of their land would be adopted without change. DB codified as well as possible the status in 1086 and formerly (in King Edward’s time*) noting some changes in ownership, but with general acceptance of the measurement of the land. (* Tempore Regis Edward I) There is practically nothing directly imported from Normandy which supersedes the existing system found by the Normans on their arrival, for a Saxon vill was run on the lines of a Norman Manor (H Weldon Finn). At the top was the Lord of the Manor (previously a Thane). Then came villeins (or geneats), tenants holding possibly 30 acres; then serfs (or theows) who were landless men or slaves. Bordars or cottars held 5 acres. Middlesex and Hertfordshire ‘Middlesex’, is thought to have comprised independent Angles and Saxons and surviving Romanised elites. Several hundred years later the country divided between Mercia, Wessex and the Danelaw and the region was again shifting middle ground. This is the land that Domesday Book investigated. The west boundary of Middle Saxon territory was along the valley of the River Colne and thence along the later Hertfordshire border with Buckinghamshire. ‘Haemele’ seems to have been the north west extremity of East Saxon territory. The later parish was 12,000 acres and it is thought that Haemele was a sub territory (pagus) of Verulamium. The western frontier of the Middle Saxons therefore ran from Hemel Hempstead and Harefield in the north, to Staines on the Thames. Nearby Rickmansworth was also a large parish of about 10,000 acres with (Watford) Cashio 10,800 acres. Hertfordshire emerges from the subdivision of Middlesex in about 1011. Hertford, the borough town, had been garrisoned as a fortress by Edward the Elder in 912. Now it was the base of operations against the Danes of Bedford, Cambridge and Huntingdon. It was supported by Berkhamsted also strategically sited. DB records 46 burgesses ‘from London’ living in St Albans and 146 burgesses in Hertford, possibly military personnel, evidencing the security needs of both places. A hide was generally 120 acres but there were exceptions. The number of hides to a hundred was variable. A hide was deemed to be the amount of land to support a family and this depended on the quality of the land. Hertfordshire comprised ten hundreds, reducing to nine when Danais and Tring merged into Dacorum (of the Danes). A hundred was the first fundamental form of English government. Its purpose commonly was to provide a hundred fighting men, corresponding also to a hundred families, and to the hundred patches of land that supported each family. The text that is called the Tribal Hidage is a late corrupt copy of ancient administrative lists of the Mercian kingdom and its subject states. Sometimes flexible, the hide became the standard English unit of land measurement. A House of Benedictine Monks The land granted in 793, from Offa to the Abbot of St Albans, included 34 ‘mansiones’ in 12 ancient parishes, comprising most of the later hundred of Caishio, forming a triangle with Sandridge as the apex, and the ancient boundary from Rickmansworth to Barnet as base. The south boundary is close to Grim’s Dyke, a territorial line going back at least to the Catuvellauni and the future division between Hertfordshire and Middlesex. The charter also included 6 additional mansiones in Stanmore, part of the Forest of Middlesex. (These charters are taken from Cott, MS, Nero, Di, folio 148 and 148 d) “The gift of so many ‘manses’ or ‘mansiones’ did not indicate a strictly defined area but probably waste land such as all the south and south west parts of Hertfordshire. King Offa’s charter suggests that the lands granted to the Abbey were woodland, for on it he forbids anyone to do harm either to the church or to the woods (silvis) belonging to the monastery.” Rickmansworth was also given to the Abbey and is described as “a small market town occupying a low moorish situation near the confluence of the Rivers Gade and Colne and a small rivulet, the Chess, which flows out of Chesham and Flaunden in Buckinghamshire.” It is a large parish of about 10,000 acres. DBi, 136a, Rickmansworth, 15 hides or 1800 acres suggests later separation perhaps from open heath and woods. In the 11th and 12th centuries, Caishio was Albaneston or St Albans Hundred, and included Sandridge, Abbots Langley, Chipping Barnet, East Barnet, Elstree, Redbourn, Sarratt, Rickmansworth, Watford and St Albans City. It acknowledged the ecclesiastical nature of much of the hundred. Some southern holdings in Dacorum were transferred to Albaneston. ‘Dacorum’ was itself a recent ‘affectation, in which classical names were allocated to later barbarians’. For government purposes some of the St Albans holdings were later detached and restored to Cashio. Cashio, Bushey and Rickmansworth The entries from DB are Cashio 20 hides, Bushey 15 hides, and Rickmansworth 15 hides. Details follow. The date of DB is 1086; data collection may have varied but not by much. Three Frenchmen are listed in the DB entry for Cashio. They may have been officials of the monastery, reeves, bailiffs or millers. Since Cashio was held by the Abbot of St Albans, he was the titular Lord of the Manor. The town of Watford is not mentioned by name, and recent thinking suggests it did not exist as a settlement in 1086. Further, references to an early market in the time of Henry I (1100-1135), or Henry II (1154-1189) require some caution. The new parish church was built in 1230, and the under-used land owned by the Abbey nearby and downhill to the river might have been stimulated for development by the provision of the market hall and other facilities by an investment minded St Albans Abbey. The land is rated for 20 hides; the Abbot has 19 of them There is woodland for 1000 swine Turold held one hide of Goisfride de Maneville in Cashio (Geoffrey de Mandeville) Cashio has extensive native woodland which would have included Whippendell Woods, Oxhey Woods and Harrow Weald part of Middlesex Forest. One plough comprised 8 oxen. Sufficient land for 22 ploughs Common pasture included Watford and Cashio Common, Croxley Moor and Watford Heath The lay monks living at Wiggen Hall were experienced in reclaiming land previously forest and marsh and protected their fields with prickly hedges to keep the oxen out and giving rise to the names of two parishes Oxan-gehaege (oxen hedges) and Bysc-gehaege (bushy hedges) now called Bushey and Oxhey. The four mills are likely to be Wiggenhall (later silk mills), where the first bridge may have been built over the Colne, Cashio Mill, Grove Mill and Oxhey (Hamper Mill). Corn was sent to the Abbot’s mills to be ground. A ‘high bridge’ existed over the Colne near More Hall. The cost of milling corn was a source of grievance in the later Peasants Revolt. There was probably a small vill (hamlet) near each mill, ie. Brightwells by Hampermill. Anglo Saxon Place Names A number of early Saxon settlers are remembered in local settlements as follows: Baecce - Batchworth Heath - the farm of Baecce in Rickmansworth Colne - various spellings, Coln, Colesna - ancient name predating Saxon times The land was ‘empty’ in 793 AD. There had been forty Roman villas in the region including Gadebridge, Bricket Wood, and The Moor. The population of Britain had dropped and the extent of land drained declined as maintenance of channels and culverts was not carried out. New Saxon arrivals must have assessed the opportunities from abandoned and wasted land. Were any of their descendants among the recorded villeins, cottars and bordars of Cashio, Bushey, and Rickmansworth? Bordars were men associated with the lord of the manor and also smallholders; cottars were cottagers with about an acre or so of land they could use for domestic purposes; the villans or villeins were associated with all sorts of duties around the ‘vill’, a local region which might contain a scattering of houses over a wide area. LANDHOLDERS LISTED in DB HERTFORDSHIRE

Cashio – DB Herts 10.16 – Owner St Albans Church The Abbot holds Cashio himself. It answers for 20 hides. The Abbot holds 19 of them 3 Frenchmen and 36 villeins with 8 smallholders have ploughs 4 Mills @ 26s 8d; meadow for 22 ploughs; pasture for the livestock Total value 28 pounds; when acquired 24; before 1066 - 30 pounds Bushey – DB Herts 33.2 – Owner Geoffrey de Mandeville Geoffrey holds Bushey himself. It answers for 15 hides. Land for 10 ploughs. 10 villeins with 1 Frenchman and 8 smallholders have 5 ploughs; a sixth possible. 2 Mills @ 8s; pasture for the livestock Total value is and was 10 pounds; before 1066 – 15 pounds Rickmansworth – DB Herts 10.15 – Owner St Albans Church The Abbot holds Rickmansworth himself. It answers for 15 hides. Land for 20 ploughs. 4 Frenchmen and 22 villeins with 9 smallholders have 14 ploughs; a further 1 possible 1 Mill @ 5s 4d; meadow for 4 ploughs; from fish 4s Total value 20 pounds 10s; when acquired 12 pounds; before 1066, 20 pounds 33. After the Conqueror 1. Roads It is said that all roads lead to Rome. In what later became Hertfordshire, when Middlesex split in half, all roads seemed to lead to St Albans. Ermine Street was the major road between London and York, running along the Lea Valley. At Royston on the county border, it is met by the ancient cross Britain highway, the Icknield Way. Watling Street, west of Ermine Street, in a nor-nor-west direction from London to St Albans was arguably the most important road in England from Kent to London, to Sulloniacis (Bushey Heath), to St Albans and Dunstable where it too met the Icknield Way, before leading to Wales. Akeman Street, seems to have been a link from Verulamium, crossing to the valleys of the Gade and Bulbourne via what became Hempstead, Berkhamsted, and Tring. It anticipated both the Grand Junction Canal, and London North Western Railway. The road linked Aylesbury, Bicester and Roman Cirencester. Between these radials, lanes, paths, and byways would one day be part of the modern county network. This land of woods and fields, of rivers and hamlets, is crossed and double crossed by old and new roads, a web that speeds commerce to London, soldiers to trouble spots, pilgrims to the shrine of St Alban, farmers to market, and courtiers to the king. This road later developed south to what we now know as Watford to complete a natural route from London, once the ancient River Colne was safely bridged. The development of the town itself was accelerated and encouraged the construction of the turnpike road called the Sparrows Herne Turnpike (see below). On the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539, the lands of St Albans Abbey, including the manors and estates in Hertfordshire were acquired by Henry VIII’s courtiers, servants, business associates in the start of a hundred year property boom. Lord Burghley lived at Hatfield House. London merchants resided in the nearby country. Great highways were narrow, winding, impeded, unsurfaced, undrained and potholed. Turnpike trusts were created along main thoroughfares, responding to the need for improvement. By the middle of the 18th century major roads in Hertfordshire were controlled by these turnpikes, paying for maintenance and improvements out of tolls levied on users. Awkward corners were straightened out, gradients eased, roads widened, surfaces improved. In the early 19th century, Thomas Telford and John McAdam introduced skilled road design, and with better horses the speed and comfort of travel was revolutionised. In 1757 in a triumph of private enterprise, the Earl of Salisbury at Hatfield House, and the Earl of Essex at Cassiobury in Watford combined to construct and maintain a new road from Hatfield through Watford to Rickmansworth, to Reading to join the existing road to Bath. Thus they by-passed the dreary journey to London. 2. The Canal The Grand Junction Canal, later Grand Union Canal, from the Thames to the Trent, was commenced in 1793 to connect London with the Midlands. Built by hand, it was fully open by 1805, and the trade of the country began to travel along it. The speed limit was set at 4 mph. It encountered little opposition from key and influential landowners, the Earl of Essex at Cassiobury, and Lord Clarendon at the Grove. Flowing through both estates in 1819, the canal was eventually seen as a complement to the countryside. By 1860 a regular service of steam narrow boats ran both day and night. The journey from Watford to London took about a day and trade was varied, but mostly coal. Steady growth in London encouraged an important trade in building materials. But like the stage coaches, the canal would suffer from the coming of the railway to Watford. The line of canal threads its way through a network of lakes south of Rickmansworth as it follows first the River Colne, then the Gade to Hemel Hempstead, the Bulbourne to Berkhamsted and Tring, flirting with each river in turn, drawing water, providing an enhanced landscape of quiet locks and bridges and sleepy lock keepers’ houses, to add to the country’s ancient mills, a waterway for pleasure and distant industry. The canal does not concern itself much with Watford, dreaming through the estates of the nobility to the north, but focuses on long distance travel to northern industrial centres. On the way paper making factories spring up at Croxley and Hemel Hempstead, where ikons of youthful correspondence are created, enshrined in matching paper and envelopes with which we write earnestly to girls at the Grammar School. Large reservoirs become sailing lakes and bird sanctuaries. At the entry to Hertfordshire at Rickmansworth, the canal is 127 feet above sea level. At Tring on the county boundary with Buckinghamshire in the Chilterns, the canal is 382 feet, a rise of 255 feet in approximately twenty miles. Ancient Tring, at yet another junction of the Icknield Way, and Roman Akeman Street, is for a time lifted out of the past into the modern world of 1792 as the canal, through many locks, reaches its greatest height. Elstree Reservoir is one of the largest sheets of water in the county. It was constructed in about 1796 to feed the Grand Junction Canal, and is a major civil engineering achievement which still dominates the landscape. In the Gade and Bulbourne valleys the canal is often overhung by beech and willow or traversing open fields. 3. The Railways The new London to Birmingham Line (L&BR 1832-1846) ran through Watford, Berkhamsted and Tring on its way to Birmingham. In June 1837 the line was opened as far as Boxmoor and carried 40,000 passengers in 28 days. It continued to Tring by October 1837 through Berkhamsted and a year later concluded at Birmingham. It was one of the first intercity lines in the world. It then became part of the London and North Western Railway, and the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS). Watford was transformed from a market town to a major commercial centre stimulated by its proximity and access to London. The railway line was 112.5 miles long which at that time was the longest continuous stretch of railway to be found in the world. The line was engineered by Stephenson, who selecting his line from Euston to Birmingham had to choose his route bearing in mind the topography and geology of the land through which he wished to pass. More difficult were the objections of the landowners. Stephenson originally wanted to place his key junction further north at Tring, where the gap in the Chiltern Hills would allow easy access to Aylesbury and skirting high ground, east to Bedfordshire. When that land was found to be unavailable he settled on Watford. His original plan was to route the railway to the west of Watford avoiding high ground to the north of the town and the cost of tunnelling. It would have saved expense, effort, and several lives. But opposition from traditional landowners whose ancestors had welcomed the prospect of the canal included the Earls of Essex and Clarendon, whose lands included Cassiobury Park and Grove Park, were on the proposed line. So the new line was drawn in a quarter of a circle to the east of the town. The tunnel north of Watford was 1 mile 170 yards long and 24 feet wide. The crown of the arch was 25 feet high. Many were injured and ten men killed during the excavation through dangerous chalk. A fourth main line was laid and a second tunnel cut, alongside the original one to the north of Watford. A third track was added in 1859 and a fourth by 1875. The prospectus offered the following inducements: ‘First, the opening of new and distant sources of provisions to the metropolis; second, easy, cheap and expeditious travelling; third, rapid and economical interchange of the great articles of consumption, and of commerce; lastly, the connection by railways, of London and Liverpool, the rich pastures of the centre of England, and greatest manufacturing districts; and through the port of Liverpool, to afford a most expeditious communication with Ireland.’ In 1878 goods traffic was accepted at Bushey Station. The Metropolitan Railway reached Rickmansworth in 1887. Croxley Green had a station in 1912, Willesden in 1913. In 1922 the LNWR ran the first electric services from Euston and Broad Street to Watford, Croxley and Rickmansworth. Both the Metropolitan Line and the London North Eastern Railway (LNER) were using Watford by 1925. Watford was in every sense a Junction. By 1900 the expanding town needed improved facilities. Seemingly closer to London, Watford was growing faster than most parts of England. The quiet market town of Watford was becoming more important than the ancient cathedral city of St Albans, historically its landlord and master. The canal helped in the construction of the railway by transporting equipment to nearby sites, and the first locomotive seen in West Hertfordshire was brought in sections by barge from London. William Henry Smith (WH Smith) was the official book stall contractor, first to the London and Birmingham Railway and then to the London and North Western Railway from 1848. He became a prominent early Oxhey resident at the farm and mansion known as Oxhey Place, subsequently the home of Mr Blackwell of pickles fame. In the 1870’s the London and North Western Railway was boosting Watford by offering a free 21 year season ticket to house buyers over a certain purchase price. The ticket was tied to the ownership of the house. In 1913 the new electric line was opened. It had required more track widening, an upgrade of the station, and the consequent construction of the new electric line viaduct. In the 1920’s Bushey Station was the busiest between London and Watford. Conclusion The revolution in transport brought the district a social prominence. Watford would soon become the largest agricultural and manufacturing centre in the county, eclipsing the City of St Albans. Industry was given a big boost. Printing, engineering, brewing, mills, and industrial estates depended on efficient transport systems. Lastly like St Albans, Watford would benefit not only from jobs created by the railway and arterial roads, but also provide accommodation and social services, schools, hospitals and infrastructure to these new residents. Watford had become a leading railway town, part of the artery from London to Birmingham, to Liverpool, and eventually Scotland. BUSHEY AND OXHEY, WATFORD HEATH AND BATCHWORTH HEATH Background Hertfordshire slopes gently from north-west to south-east, from the Chiltern Hills, to forests, moors and farms. In 793 AD King Offa granted extensive ‘vacant land’ to the Abbots of St Albans. Included was Rickmansworth on the north side of the River Colne, and Batchworth, Oxhey and Bushey, on the south. The lands of Watford, part of the Hundred of Caishio, were also included. The new market town outgrew the cathedral city which had once owned the very land on which Watford and its suburbs sat. This land had early on been farmed by lay priests, who built bridges over streams, turned local heaths, woods and water meadows into fertile pasture and enclosed fields. In the 1880’s, slicing vertically across the map, the London North Western Railway carved its way through the West Hertfordshire countryside, dividing Watford in the north west from Bushey over the river. It also effectively truncated the Saxon Parish of Oxhey. The massive railway embankment and viaduct known as Bushey Arches became a permanent barrier when it was built in 1836/7. The older natural boundary was the River Colne which separated Watford on the north bank from Batchworth Heath, Oxhey, Watford Heath and Bushey to the south. Because of the difficulty of tunnelling through the massive upland of Bushey Heath and the Weald, Stephenson selected a new line swaying gracefully westwards over the farms of the Harrow area, into Watford. From Euston new railway halts were established serving emerging communities with little known names, some simple brick and timber shelters in the agricultural landscape, and from the East End of London communities of prosperous mobile city dwellers sought a new life in the rural environs of the land opened up in the north west by the railway. For a while Watford was the first stop after Euston. Then a score of new place names were selected, often taken from farms and country houses like Carpender’s Park, the stop before Bushey, where a stilted platform was erected to raise passengers to and from the trains. As the line cut its way through woodland in a cutting 130 feet deep in the chalk of Oxhey, new bridges had to be built by which carts and travellers could cross from one part of the district to the other. Oxhey Road did not yet exist but the path from Wiggen Hall linked up with Oxhey Lane across Watford Heath. The new Oxhey Road bridge across the chasm helped to both access rustic Watford Heath, and define its separate identity. This graceful structural brick bridge was formed of three fine segmental arches, the centre one springing from two very lofty piers at an elevation of twenty-five feet and the two side arches abutting the slopes of the excavation. A second brick bridge served the other footpath from the vicinity of Oxhey Brook across rising wheat fields to the railway and along a foot path which now ran along the top of the railway, north to Watford Heath, and south to Carpenders Park, and across the brook to the mansion and farms of Oxhey Place. There were small and wider tunnels through the embankments to facilitate the movement of occasional pedestrians, cattle or crops. Approaching Watford through Oxhey from the south, Stephenson intended a long tunnel from north of Carpenders Park to Bushey Station. Discovering the soil was unsuitable, he decided on this deep cutting which was cheaper. 372 cubic yard of soil were excavated and used to build the outer surfaces of the embankments towards Watford. Watford Heath like Watford Fields was once part of a greater open field system which was enclosed. The new cutting and the development of farm land would seem to shrink the locality to a collection of pubs and houses around the village green. In fact it gave Watford Heath greater definition and identity. Bushey Station opened on December 4 1841 with three trains to London at 8.21 am, 9.36 am, and 12.07 pm. Trains returned at 3 pm and 6 pm. Close to Bushey Station was the new church of St Matthew’s Oxhey, now isolated from the eastern part of Oxhey, New Bushey and Watford Heath. The church had been sited with a view to serving future residents on then undeveloped land to the west. New Bushey was virtually the child of the railway. There had long been cottages near the Arches and up the hill towards Bushey. A toll gate was removed in 1872, its position marked by an iron pillar bearing the words ‘Sparrows Herne Trust’. Rebuilding the line for widening in 1874, a booking hall was provided on each side and a convenient subway linked the parishes. But not until 1 December 1912, bowing to the influence of the Railway on the divided suburbs, was the station at last known as ‘Bushey and Oxhey’. The electric line from London to Harrow reached Bushey and Oxhey in 1913 with a further station at Watford High Street. Civil Engineering Nearer to Watford, carrying the main line from Euston is the massive five arch brick viaduct about thirty-five feet high which takes the main line over the River Colne, the middle arch spanning forty feet. A mile nearer to London is the famed Bushey Arches, a stone faced twenty-five foot high brick viaduct spanning the road complex between Bushey and Watford over Chalk Hill. There are five arches with a span of forty-three feet each. The centre arch is oblique since by Act of Parliament the course of a road, over which a railway passes, cannot be altered. The length of the viaduct is 370 feet. In 1837, the LNW Railway had only two tracks but as noted above steel additions were made in 1859, 1875, and the latest modification was in the early 1960’s. During the Second World War several unsuccessful attempts were made to bring down Bushey Arches by bombing to cut the line to Scotland. Strategically therefore a Barrage Balloon hung over the River Colne nearby, as a deterrent to German planes flying up the Colne Valley to target Watford. In 1913 the new electric line opened, requiring more track widening, an upgrade of the station, and the construction of the new electric line viaduct. In the 1920’s Bushey Station was the busiest between London and Watford. The design and construction of many graceful bridges over the Grand Union Canal and the Rivers Gade and Colne enhance the countryside. The towering brick viaducts which dominate the landscape in the Colne Valley and the long railway tunnel to the north of St Albans Road are significant engineering achievements by any measure. Watford, market town and manufacturing centre had become the largest town in the county. The South Watford Ordnance Survey Map of 1896 indicates potential sources of local building materials, a chalk pit, lime works, brickworks. Interestingly, it also listed existing householders in New Bushey by name. St Albans and Watford were now seen as convenient residential centres for workers in London who travelled daily by train to their places of employment. The London to Birmingham Railway crossed the turnpike where the road to Watford across the river joined those from Oxhey in the west and Bushey in the south. The local station was called Bushey and the new railway suburb up the hill became New Bushey. But the railway line had not only empowered Bushey, slicing its way through the Saxon parishes, it separated districts linked by history and associated in royal charters. In 1947 a new housing estate was commenced on the farm lands of the former Oxhey Place, once the home of Gilles Saint Clare, whose house was known as Sinklers or Sinkley. Other prominent owners were WH Smith, the bookseller, and Mr Blackwell of Crosse and Blackwell. But the southern boundary of Oxhey Parish defined in Saxon times itself recalls the line of the mysterious Grims Dyke. This was the boundary of Oxhey and ‘the limit of the franchises of the Abbey of St Albans’ as granted by King Offa. In the centre of this fertile land were the extensive Oxhey Woods and the mansions of Oxhey Place, Oxhey Lodge and Oxhey Hall. Carpenders Park, New Oxhey, or South Oxhey, what's in a name. Sources Watford & New Bushey 1896, Hertfordshire Sheet 44.06. Commentary by Mary Forsyth

38. The Town of Watford Expands

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||